Co-founded by Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich in 2012, 10x10 Photobooks foster engagement with the global photobook community through the appreciation, dissemination, and understanding of photobooks. The PGH Photo Fair has partnered with 10 x 10 Photobooks on all their previous touring reading rooms, including in 2019 for How We See: Photobooks by Women, which presented a global range of contemporary photobooks by women.

Follow-up project, What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women 1843–1999, focuses on historically significant photobooks produced by women. Officially released on 1 November 2021, the book was recently shortlisted for the Paris Photo - Aperture Foundation Catalogue of the Year Award 2021.

Helen Trompeteler spoke with Olga Yatskevich about 10x10’s ongoing exploration of photobook history and the underrepresentation of women in this field.

How does your own cultural and personal background inform your approach to the photobook? Do you have a particular early experience with a photobook or reading room which inspired your engagement with this art form?

My interest in photography is fairly typical. My grandfather was a serious amateur photographer, I would spend hours looking at family photo albums and often re-arranging photographs. I spent a big part of my life moving between countries, first with my parents as a kid and later for school and work. I was constantly exploring new places and taking photos felt pretty natural. And I’ve always been a book person but my interest in photobook shaped when I moved to NYC. I started making connections with the local photo community, both in person and online. That’s how I met Russet Lederman, my partner in 10x10 Photobooks. I invited Russet and Jeff Gutterman, her husband, to come to a photobook meet-up I was organizing and talk about Japanese photobooks from their extensive collection. In a way that was the beginning of our 10x10 project.

We started 10x10 Photobooks with a very simple idea - to bring to New York contemporary Japanese photobooks, not easily available through regular distribution. We invited ten people to suggest ten photobooks published by Japanese photographers. We brought these books in a pop-up reading room and invited people to come to the space and spend time with the books. The project came together in just about two months. Our first reading room, titled 10x10 Japanese Photobooks, was launched in September 2012 during NY Art Book Fair, and was sponsored by the International Center of Photography.

Histories of the photobook have existed for some years now. For example, Martin Parr and Gerry Badger’s multi-volume history published between 2004-2014 was a high-profile series on this subject. However, the politics of selection is an important consideration. The photography and publishing industries have frequently had their histories shaped by ‘gatekeepers’ with social or financial influence. For example, Helmut Gernsheim and Beaumont Newhall wrote hugely influential books that shaped twentieth-century photo history, neither of which included many women photographers. At 10x10, your collective approach to constructing histories resists this model of selection, incorporating more democratic forums for dialogue across reading rooms, publications, and events. Can you talk a little about this underlying ethos of co-creation?

From the very beginning 10x10 was about community, collaboration, inclusion and diversity. 10x10 was about bringing together people with different backgrounds - publishers, photographers, collectors, writers, designers, curators - and various interests within photography, but with common passion - photobooks. 10x10 wanted to provide a platform for a conversation. Almost a decade later we are a non-profit organization, and our mission is the same - to foster engagement with the global photobook community through an appreciation, dissemination and understanding of photobooks.

We have completed four major reading rooms - focusing on Japanese, American, contemporary Latin American Photobooks and photobooks by women. To put these projects, we brought together a diverse group of contributors. They followed a similar format; our experts were asked to each select a number of photobooks. We also ask each selector to write a short statement to explain what brings these books together, which helps people understand the individual books and to see the connections between them.

When 10x10 produced How We See, the program of touring reading rooms relied on the tactility of the objects. In interviews at the time, Russet Lederman discussed that 10x10 didn’t include historical works due to the inability to show them and have the public interact with them. One of the aspects of the new book I love is how objects have been photographed to emphasize a wide variety of material histories and qualities. How will this translate into what is shown in the reading rooms program for What They Saw?

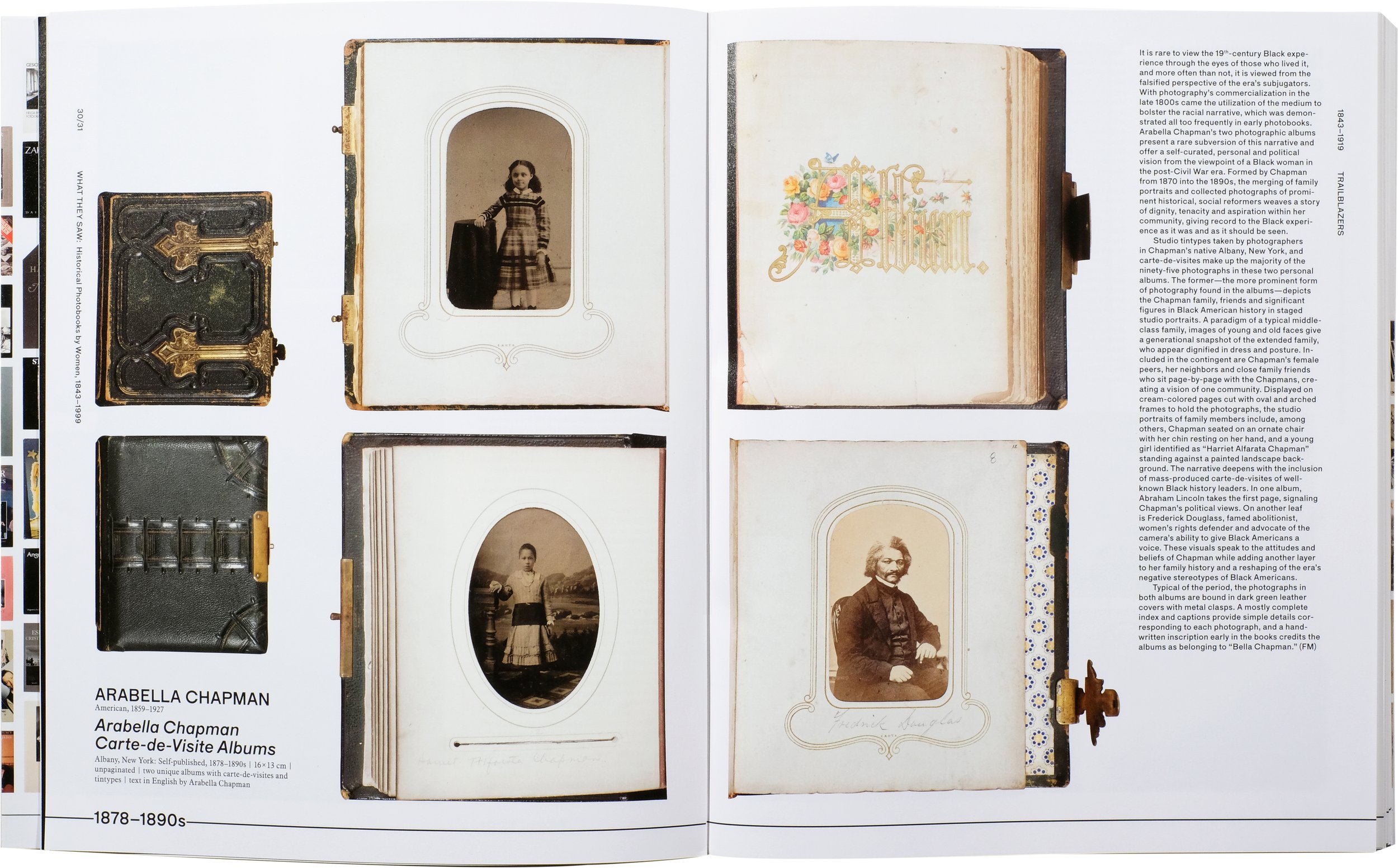

We had the photobooks included in all our previous reading rooms. Inviting people in a space where they can touch books, flip through the pages, smell the ink was always essential to us. That’s why we also donated the books from each reading room to a dedicated public library, so people continue to have access to them. Many books discussed in What They Saw are still available for a reasonable price, and we were able to purchase a good portion of them. But there is a number of rare books too, like Anna Atkins’ “Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions” (1843-1853). Some of them are unique albums, like the one put together by Kate A. Williams with the cards collected during her travels in Europe to share with friends, or a carte-de-visite album by Arabella Chapman, a Black middle-class woman in Albany, New York; her albums include photographs of friends, family, and leading abolitionists. These types of publications are unique, we hope to create flip through videos to showcase them. We also tried to illustrate them extensively in our publication. We are planning to partner with institutions that already have many of these books in their collection. Our first reading room will be in partnership with the New York Public Library in May 2022.

Arabella Chapman, Carte-de-Visite Albums, in ‘What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999’. Courtesy 10 x 10 Photobooks

To truly challenge the canon of photo history, I think it is essential to collaborate with experts from other fields – across political, cultural, and social disciplines – as all these factors work towards shaping and constructing knowledge. Can you talk a little about the selection of writers for What They Saw and whether this was a concern?

Producing a publication like this one requires a big team. We invited Mariama Attah who is curator of Open Eye Gallery in Liverpool to write an overview essay. To address the current photobook history, she brings the metaphor of a popular Mercator projection that distorts the relative size of landmasses. She articulates a number of questions we are trying to cover with this project. The book has ten chapters, and we brought scholars, both western and non-western, to write them. These chapters also map key political, cultural and social events that influenced those decades, and briefly mention the books discussed in detail for that chapter putting them in that context. Carole Naggar is a photography historian, and also a writer and poet. Elizabeth Cronin is a curator at the New York Public Library. Paula Kupfer brings a Latin American perspective, while Michiko Kasahara offers a perspective from Japan. Jörg Colberg, originally from Germany and now based in the United States, is a writer, photographer, and educator.

A huge amount of communal effort went into this publication. Many people contributed to this publication; our acknowledgement list is pretty long. We also had a number of PhD students and researchers who contributed drafting book blurbs. Our designer, Ayumi Higuchi, had an enormous task of putting together all the elements, and I think she did an incredible job.

There are many practical and structural reasons why women photographers have been omitted or underrepresented in history. Many male-owned nineteenth-century studios relied on female labor, but their names and histories have been largely unrecorded. Sometimes women photographers operated under a pseudonym, or their change of name through marriage means their lives become harder to trace through archival records. As periodicals and the magazine industry boomed during the early twentieth century, images were often reproduced uncredited. Reclaiming and working with historical material within photobooks can be a way to address these omissions. Please can you talk a little about this theme of archival loss or absence - and perhaps give a few favorite examples of innovative photobooks that have addressed this specifically?

There were a number of factors that kept women’s names from the proper acknowledgment in the publication and public eye. To expand this conversation and widen the frame, we had to reconsider our definition of a photobook, so we included individual albums, maquettes, zines and pamphlets. But we are expanding this conversation to include not only women, but make it as inclusive as possible.

Take for example, Isabel Agnes Cowper, for over 20 years she was the official photographer in the South Kensington Museum but was not credited in any of the publications and remained neglected until recent research and the scrutiny of the museum archives. Now she is recognized as the first woman to hold the title of official museum photographer. Her photographs document museum exhibitions, objects in its collections and the construction of museum facilities. In our publication we included one of the earliest volumes illustrated with her photographs, “Catalogue of the Special Loan Exhibition of Decorative Art Needlework Made Before 1800” published in 1874.

There are many forms of individual self-publishing. But more broadly, power dynamics are often involved in every stage of the photobook process – editing, captioning, design, circulation. Editing and sequencing especially rarely receive critical study within the history of photography. Many post-war historians emphasized notions of the master photographer at the expense of this broader contextualization of the medium. How can we encourage an approach that moves away from solely focusing on notions of single authorship to acknowledge these wider contributions and contexts?

Women have consistently contributed to the photobook history, and as early as the mid 18th century. However, their contributions were often neglected, misrepresented or diminished. What They Saw starts to identify where we might find these voices. It is important to keep questioning dominant historical narratives, as individual contributions too often get lost or overshadowed. To represent these fragmented and incomplete histories, we included timeline entries that need further research.

There are examples of women supporting their husbands in their commercial photographic endeavours, and hardly getting any mention. In the 1860s in Japan, Ryu Shima had a studio with her husband and most likely contributed to two albums, her name is not credited. Ashraf os-Saltaneh, an Iranian princess and one of the earliest women photographers in the country, kept her husband’s diary and most likely used her photographs for illustrations. There are so many examples. Uncovering and sharing these stories help us to see a bigger picture.

Zofia Rydet, Mały człowiek, in ‘What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999’. Courtesy 10 x 10 Photobooks

Especially since the 1970s, women have found a platform at the intersections of theoretical, political, and autobiographical writing in photography. Even before this, photographers such as Dorothy Wilding and Madame Yevonde safe-guarded their place in photo history by writing memoirs, seeking empowerment by telling their story in their own words. So, I’m interested in how women have had to write themselves and their careers into photo history. Jo Spence’s undergraduate thesis was recently published in full for the first time. This exciting revisiting of past visual texts encourages a much richer history and new opportunities for contemporary dialogue. The use of language is an integral part of who is represented and how. Therefore, please can you talk a little about this relationship – how do you see these intersections between life writing and the traditions of the photobook?

Gisèle Freund wrote the first Ph.D. on photography in 1936, and a couple of years later Lucia Moholy, Both a photographer and a scholar, wrote “A Hundred Years of Photography”; it sold out immediately, in forty thousand copies. It was 1942, when Elizabeth McCausland, an American historian and art critic, wrote one of the first essays on the still new medium of the photobook titled Photographic Books. Sadly, her legacy got forgotten over the years, her essay wasn't referenced in any of the recent anthologies. When we launched our How We See project, we also reprinted the essay and had copies available during the reading rooms. Kristen Lubben, in her essay Partial Histories: Looking at Photobooks by Women for “How We See”, talks about McCausland and her contribution.

A potential critique when drawing attention to creative practice on the grounds of gender alone is that it is, in a way, reductive. The statistics you gathered while producing How We See, and regularly shared by groups such as Women Photograph and Guerilla Girls are irrefutable. Nevertheless, speaking in binaries between male and female gaze can be problematic. How can we make these discussions as inclusive as possible, incorporating non-binary and genderfluid identities into these discussions of photobook history?

Our How We See project, required that all photography contributions in a selected book are women, and those who identify as women. We used the same approach for What They Saw. As we explore the photobook history, inclusivity is one of our primary goals.

The potential of movement that is inherent with photobooks have made them so central to political movements, including second and third-wave feminism. Zines, newspapers, leaflets, pamphlets can all be shared easily, sent cheaply, travel between countries – they are an effective way of circumventing the establishment. Can you talk a little about your views on what constitutes a feminist photobook? How do you see the potential of photobooks as agents of such political action?

What makes a photobook feminist? There is no simple way to define this. In early years access to publishing was rather privileged, and many women who had this access used it to state their independence, economic, sexual or artistic. Today photobooks are versatile, inexpensive and democratic. They can easily travel, share ideas and ultimately empower.

There are definitely a number of photobooks I would consider as an example in What They Saw. From a late 19th century album made for the Women’s Social and Political Union by Christina Broom and Isabel Marion Seymour with portraits of the Suffragettes to Elsa Dorfman’s “Elsa’s Housebook: A Woman’s Photojournal” which documented the rich social life of a young woman in the 1970s and Abigail Heyman’s "Growing up female: a personal photojournal", giving us a frank portrait of what it means to be female in the United States in the 1970s.

I think a great example of political action is a photobook, a pamphlet to be precise, by Alice Seeley Harris titled “The Camera and the Congo Crime”. Published around 1906, it is one of the earliest examples of a humanitarian photographic campaign. Harris’ images reveal the colonial atrocities endured by the Congolese people. It played a key role in bringing attention to these atrocities committed under King Leopold II.

Or another, perhaps more known book, and an example of both feminist and protest book is “Immagini del no” (Images of No) published in 1974, with photographs by Paola Mattioli and Anna Candiani. It was published in the wake of the Italian referendum to repeal an earlier law legalizing divorce. It made a direct appeal for political change in women’s issues.

Christina Broom and Isabel Marion Seymour, WSPU Postcards Album, in ‘What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999’. Courtesy 10 x 10 Photobooks

Paola Mattioli and Anna Candiani, Immagini del no, in ‘What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999’. Courtesy 10 x 10 Photobooks

Many factors impact women’s ability to sustain a creative practice – including class, money, domestic and caring responsibilities. The business aspects of women’s creativity are often completed neglected in photo histories. Historically, there has often been a snobbery around art-making and book-making being seen in this context of commerce. The reality is that to live creatively is often to live fragmentally across many different models of working and living. Does What They Saw invite a provocation to think differently about how we view success? Or, indeed, evaluate and record success within history?

How do we define success? What is our criteria for progress? In early years only women with privileged social positions were able to pursue photography. They were married to someone or came from privileged families. (And obviously, there were other factors, outside gender.) They had the means to purchase equipment, or to learn photography at first as a hobby. These women were trailblazers, they paved the way for others, and considering the context in which they worked, their contributions are extraordinary.

Each chapter in our publication sets the historical context for the books discussed within it. What are the factors that contributed to making certain books possible? We spent a lot of time searching for photobooks by Black women made between the 1960s and 1980s. We don't know how many women tried to publish books in those years, but as we talked to people it became clear that there was simply no funding for these books. “The Decorative Arts of Africa” by Louise E. Jefferson, released in 1974, is a rare example of a book that did find support. Jefferson was also the first Black woman with a director’s position in the publishing industry. Has that had an impact? These are the questions we are bringing up.

In the past few years, a number of great photobooks were published showing the body of work that was 40 years old, and just did not find recognition it deserved at that time.

Presenting diverse ethnic, cultural, and geographic backgrounds has been central to What They Saw from its inception. How can we work to ensure against future gaps and omissions in photobook history, in particular the lack of access, support, and funding for photobooks by non-Western women and women of color? How do you think publishers can better support a range of visions that are non-Western?

When we started working on How We See, we conducted research to get an idea on the representation of photobooks by women. The numbers were quite shocking. Photobooks by women made up only 10.5% of the entries in the six major “book-on-books” anthologies, three major photobook publishers had only 16.2% of photobooks by women in their online titles. However, I think if we look at the past three years, we will notice a shift. I think the conversation, on different levels, is very important. It is essential to have editors who are sensitive and consider different voices. We need to engage designers with various backgrounds. We have to continue to advocate for inclusivity within the high-profile sectors of the photobook community. As one puts together exhibitions, publishes photobooks, organizes fairs, acquires books for libraries, manages awards, let’s make sure the process is inclusive. The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem is not that they are untrue, but that they result in incomplete narratives.

Ellen Kolban Thorbecke, People in China: Thirty Two Photographic Studies from Life, in ‘What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999’. Courtesy 10 x 10 Photobooks

Lesley Lawson, Working Women: A Portrait of South Africa’s Black Women Workers, in ‘What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999’. Courtesy 10 x 10 Photobooks

The identity and interests of collectors play an essential part in shaping histories. The MUUS Collection supports What They Saw and its associated research grants. Please can you talk a little about how this relationship with the MUUS Collection started and has evolved? What can you tell us about this year’s research grants and what to expect regarding future programming relating to them?

10x10 Research Grants on Photobook History was initiated and administered by our board members, David Solo and Richard Grosbard, and were launched last Fall. We are grateful to the MUUS Collection, and their generous support of this important initiative. Their mission which is to make visible their photography collection and archives through exhibitions, scholarship, donations, licensing, and the printing of images and books, overlaps with 10x10’s.

With this grant 10x10 contributes to our mission by encouraging and supporting scholarship on under-explored topics in photobook history. The first year’s theme focuses on research into the history of women and photobooks from 1843 to 1999.

We received a good number of submissions and our jury members - Susan Bright, Sarah Meister and Ingrid Masondo – were impressed with the range and strength of research topics. While we originally planned to select two grantees, this year we decided to award three grants, $1,500 each.

Faride Mereb, an artist and independent publisher from Venezuela, will process and digitize archives of Karmele Leizaola, an important contributor to the publishing scene in Venezuela. Yasmine Nachabe Taan, Associate Professor in visual culture at the Lebanese American University, will focus on Catherine Leroy’s photobook “God Cried” (1983), a little-known book about the intense and violent conflicts in Beirut. Uschi Klein, a researcher at University of Brighton, will collect more materials about the life and work of Romanian photographer Clara Spitzer.

We will have public events to share the progress of their research with the photobook community. The high number of submissions indicates that we need to continue to support more research into the history of the photobook.

Lastly, how has your work on this project and with 10x10 Photobooks influenced your own collecting practices?

This is definitely a two-way process, our personal interests in collecting photobooks inform our 10x10 programming. Our projects come together as we engage in long conversations and brainstorming sessions, we try to determine overlooked regions and subjects, bring fresh ideas and share what inspires us. Needless to say, that through our projects I always discover new books, and purchase many of them for my own collection. Photobooks provide an opportunity to meet people, - artists, publishers, designers - support their work and share them with a wider audience.

What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999. Courtesy 10 x 10 Photobooks

To find out more the work of 10 x 10 Photobooks, visit their website or follow them on Instagram @10x10photobooks